EU Justice Scoreboard 2025: Cyprus remains a laggard in key indicators of quality and efficiency

Despite some positive developments recorded, our country ranks second to last in the standings

The recent publication of the EU Justice Scoreboard 2025 provides a new opportunity to assess the trajectory of Cyprus’s justice system within the European framework. The report’s data confirm what we have repeatedly observed in recent years: Cyprus remains a laggard in key indicators of quality and efficiency, despite some positive developments being recorded.

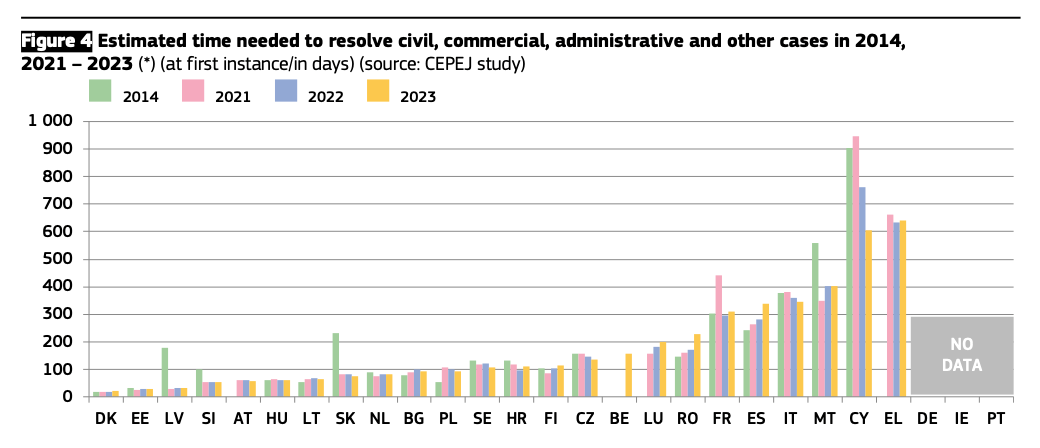

In certain areas, and particularly in the average time for case processing, a relative improvement is observed. For the first time in years, Cyprus is not ranked last in the EU, which constitutes an encouraging sign. At the same time, the increase in the number of judges indicates that the State is beginning to take into account the structural causes of delays and congestion.

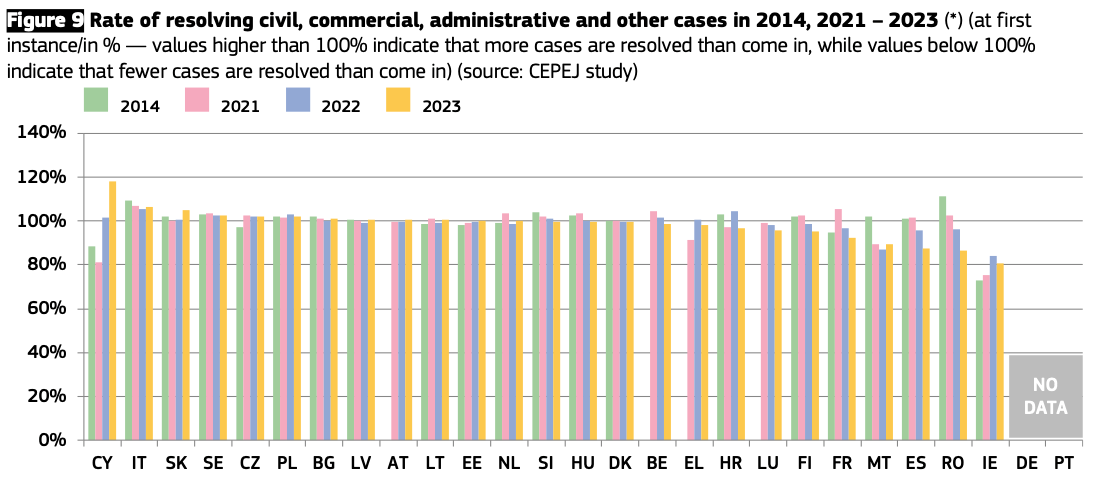

An encouraging element is the fact that in 2023 Cyprus recorded a case clearance rate of around 120%, which means that the courts managed to dispose of more cases than were filed that year. Although this is a positive development, it must be viewed in light of the years-long accumulation of backlogs. At the same time, Cyprus remains the only country in the EU that does not provide data on incoming civil and commercial cases, something that may point to a deficit in transparency and systemic capacity. The same applies in the field of technology, where Cyprus continues to rank last in terms of the use of digital tools in the courts, despite recommendations and commitments made in recent years.

Efficiency of Cypriot courts

Cyprus is no longer in last place in the EU regarding the average time for case processing. In 2021, the average time exceeded 900 days; in 2022 it decreased to 750, and in 2023 to 600. Greece now occupies the last place, with Cyprus avoiding the very bottom of the European ranking.

The ideal time for resolving legal disputes, according to European standards and in particular the EU Justice Scoreboard, depends on the nature of the case. In civil and commercial cases, completion in less than 300 days is considered a good performance, while a timeframe between 300 and 500 days is generally acceptable. In administrative cases, where complexity is higher, a timeframe of up to 400–500 days is considered acceptable. At the same time, according to the recommendations of the CEPEJ (Council of Europe’s European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice), 75% of cases should be completed within 12 months, especially at first instance.

With a clearance rate of 120% for 2023, Cyprus demonstrates for the first time the ability to process more cases than are being filed, surpassing the equilibrium rate (100%) and showing signs of a gradual easing of the judicial workload. Nevertheless, this improvement should be interpreted with caution, as it does not necessarily correspond to a reduction in the overall backlog of cases.

Quality of Justice

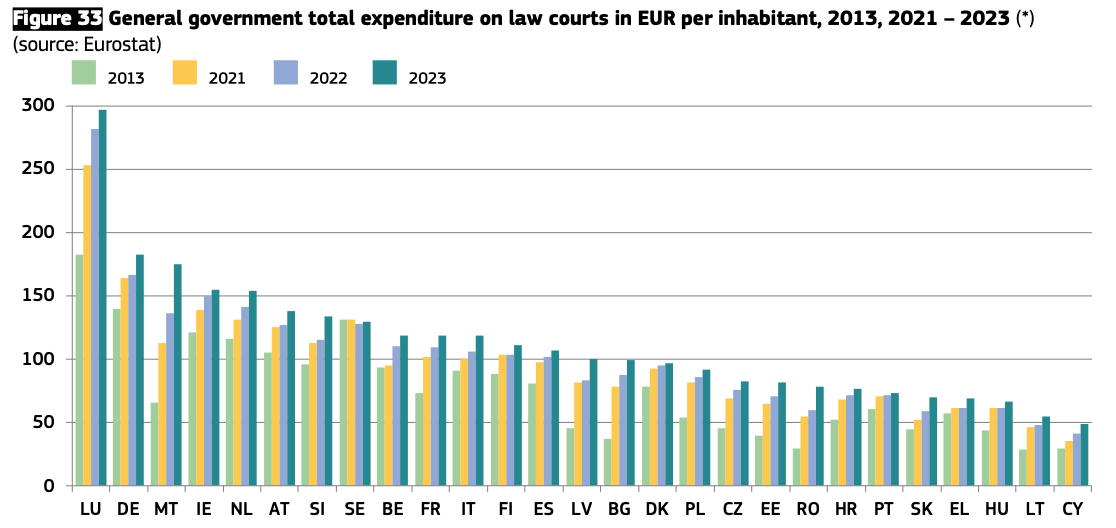

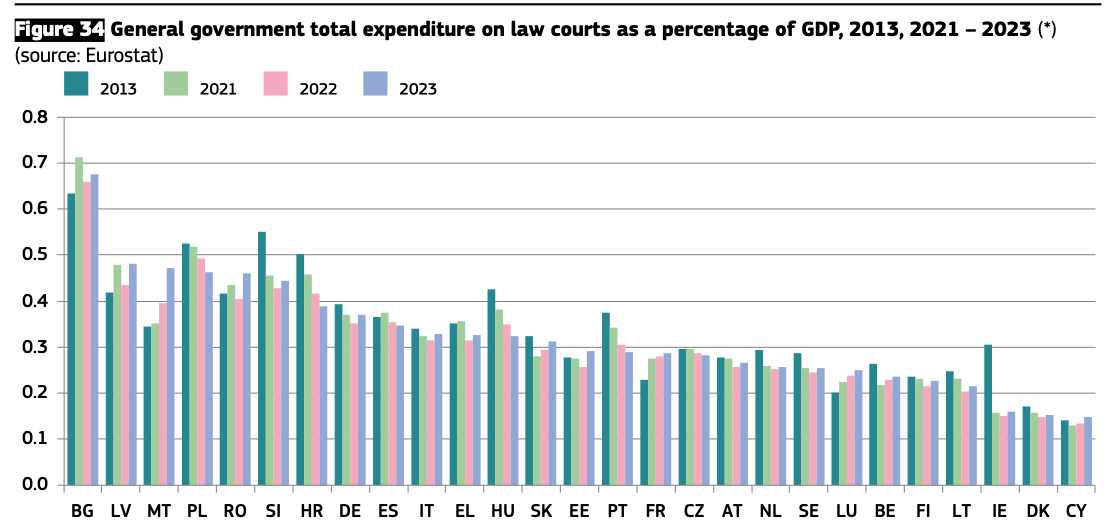

The quality of justice depends on infrastructure, technology, accessibility, and ultimately the level of investment a state makes in this sector. Unfortunately, Cyprus is once again ranked last in the EU in terms of expenditure on the functioning of courts, both per capita and as a percentage of GDP. This translates into delays, poor quality of court facilities, understaffing, and low technological readiness.

Technology represents yet another area of stagnation. Despite recommendations submitted both by the Procedural Law Unit and the Reform Committee of the Cyprus Bar Association, Cypriot courts still do not allow for the substantive use of technology. Here too, Cyprus ranks last in the EU in the field of digitalisation.

Organisational framework and human resources

The longstanding problem of inequality in the ratio of judges to lawyers seems to be starting to be addressed. The latest data show that the number of judges is increasing, partially restoring a ratio that for years had caused delays and congestion in the system (Chart 37 of the Report). When there are too few judges to handle the large number of cases generated by an overcrowded legal profession (Chart 39 of the Report), it is only natural that backlogs and delays will occur.

The increase in the number of judges, combined with the redistribution of responsibilities and the operation of new divisions, creates prospects for the system’s improvement. However, problems remain regarding the recruitment of administrative staff and the enhancement of the courts’ infrastructure. In this respect, the establishment of the Independent Courts Service is still pending.

Judicial independence: substantive or merely apparent?

Cyprus ranks 20th among the 27 EU member states regarding citizens’ perception of judicial independence. What is striking, however, is that the percentage of lack of trust increased by ten percentage points compared to the previous year. This development is particularly concerning, as it is not accompanied by corresponding institutional changes that could explain the decline.

When asked, citizens state that the reasons leading them to question the independence of the judiciary are threefold: (1) insufficient safeguards stemming from the institutional framework and the position of judges, (2) pressure from economic interests, and (3) interference by the government or political figures (Chart 51 of the Report).

Although I do not personally share the view that there is direct political intervention in judicial work, we cannot ignore the structural weakness created by the absence of external oversight of the Attorney General’s decisions. In Cyprus, the Attorney General is appointed by the executive branch and is not subject to judicial review, a point also highlighted in the European Commission’s Rule of Law Reports. Passing legislation to strengthen the independence of prosecutorial decisions is necessary, but it must provide for an external rather than merely internal oversight mechanism.

Conclusions

The EU Justice Scoreboard 2025 shows a slight improvement in case processing times in Cyprus, without, however, indicating that the system’s longstanding problems have been resolved. The absence of data for key areas, such as civil and commercial cases, constitutes a transparency issue and undermines the possibility of systematic evaluation.

Cyprus remains among the lowest-ranking countries in terms of court expenditure, technological support, and legal aid, while the lack of trust in the system reflects a deeper institutional deficit. Despite individual efforts at improvement, such as the increase in the number of judges and the introduction of new procedures, the overall picture continues to cause concern.

It is necessary to strengthen both institutionally and substantively the independence of the judiciary and to ensure the transparent, reliable, and regular publication of relevant data. At the same time, substantial and sustained investment in the technological upgrading and infrastructure of the courts is imperative. Finally, fair and effective access to justice for all citizens must remain a consistent, realistic, and non-negotiable priority.

Only then will we be able to speak of a genuine convergence of Cyprus with European standards, rather than superficial reforms.