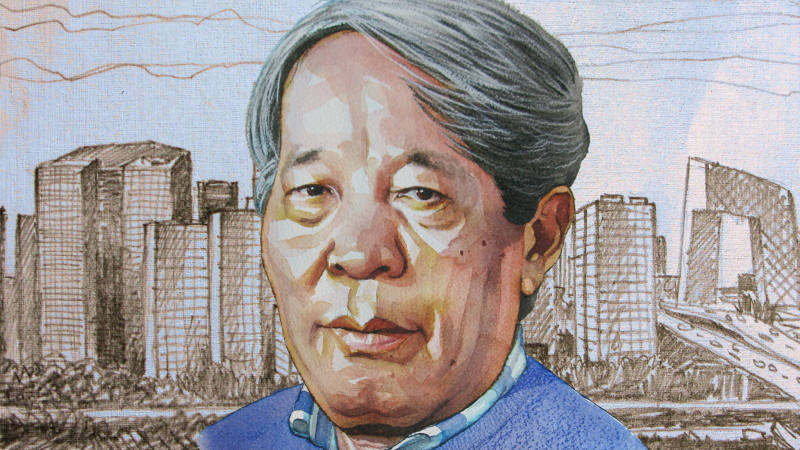

Arranging to meet Yan Lianke a few weeks ago was like walking into one of his allegorical novels, where magical accidents portend nation-changing shifts. While trying to organise our encounter, Covid-19 swept across China. Restaurants closed. Only some emails to Yan arrived, while others couldn’t be sent at all. Was this government censorship of a well-known and politically sensitive writer, or electric pulses straying on the frenzied internet? Neither of us could tell. Eventually we agreed to meet in his local park to discuss just how we might do our Lunch with the FT.

His home is close to Renmin University in Beijing, where he sometimes teaches a creative writing class. He has lived there for eight years; but in the park, every few turns the 61-year-old exclaims, “Oh. We’re here,” as if the paths were shifting under our feet.

The park is so full of people wearing masks that we can’t find a quiet corner. I ask Yan whether he is more concerned about social distancing or being overheard by state snitches. Yan is one of China’s best-known writers. Some of his most famous novels are banned, but others can be bought online, reflecting how his rudely satirical writing is warily tolerated, even under the authoritarian leadership of Xi Jinping. His essays, often fiercely political, get deleted from the web and then pop up on other blogs later, as China’s literati evade the whack-a-mole of the censors. Yet Yan tells me he has never faced serious government harassment, and he has not been forced into exile like some of his contemporaries.

It’s the snitches, not social distancing, that are on his mind. But, he adds quickly, he is only a “little writer”, so why should the Communist party be concerned by his views? “Foreign media tend to think all my books are about politics. I’m not concerned with politics; I’m concerned with the life struggles of people — Chinese people,” he says. But, he adds, “Chinese people’s life struggles are often related to power, and so quite a few books have been banned.”

When we finally find a place in the park to sit, a sandstorm whips up, and chunks of tree branches fly at us from the sky, one hitting me on the head. Beijing’s air-pollution reading is off the charts. We talk about everything from the randomness of censorship to the vastness of Chinese society. I wash the earth from my face when I get home.

The next day we have the first ever videocall Lunch with the FT.

I am 10 minutes late for our virtual rendezvous. The delivery worker who has taken my order on one of China’s ubiquitous takeaway apps has gone to the south gate of our office block. But our guards have closed the gate in order to limit the pathogen carriers, also known as humans, entering and leaving the compound. They will not let him drop off my $6 rice-and-pickles lunch deal. I call the confused courier a few times and eventually arrange another drop-off point.

Lateness is no problem for Yan: he is immensely laid-back, in contrast to the calls to arms in his essays. When I had asked him on the phone what recent pieces I should pay special attention to, he replied, “Don’t bother with any of that. Let’s just relax and talk.”

When I start up the videocall, Yan’s light-grey hair and forehead appear at the bottom of the phone screen, the camera angled at his gold-edged ceiling. I study his wine collection until he tilts the phone back down towards him. I am struck by seeing him smile for the first time: we had conversed in the park entirely behind face masks.

[…]

Read more at source

Source: Yan Lianke: ‘Propaganda is a nuclear bomb’ | Financial Times